This is the next in our series of editorial articles inspired by The Content Mix podcast. As freelance contributor Melissa Haun has edited and analyzed our interviews, she’s had to consider the grammatical and lexical changes that recent events have inspired. In this post, she dives into the connection between current events and linguistic change.

2020 has been dominated by global health crises and social justice movements. On the surface, it’s easy to see how these events have affected our lifestyles, jobs and relationships. But they’ve also impacted a less obvious, but equally important, part of our culture: language.

This year has seen some especially interesting linguistic developments, from new words and grammatical standards to semantic debates and evolving definitions. And while these changes are crucial for anyone in the field of content creation, they also emphasize the importance of language in general—with all of the power and complexity it contains.

The evolution of language

Let’s get one thing straight: language is not a fixed phenomenon.

In this article I’ll focus on English, but all living languages develop and grow—and the rules that govern them are by no means permanent. The way we speak and write is always changing, in ways both subtle and striking. Scholars throughout history have advocated for spelling reform (with varying degrees of success), and definitions are far from fixed.

Dictionaries are regularly updated to incorporate new variations of existent words and add new terminology. The most obvious example is terms related to technological developments; Merriam-Webster added “microtarget” and “deepfake” just a few months ago (along with several terms and concepts related to COVID-19).

But linguistic change doesn’t stop there.

One notable recent development is not lexical, but grammatical: the usage of gender pronouns. Many individuals and public figures have started to specify which pronouns they use (he/him, she/her, they/them), thus reinforcing and legitimizing the concept of non-binary gender through language.

Another example? Writing the word “Black” with a capital “B.” This is a widespread change that has gained considerable momentum and visibility this year. As Marc Lacey of The New York Times put it, “for many people the capitalization of that one letter is the difference between a color and a culture.”

It’s a testament to my own privilege that I had never previously considered the significance of these distinctions. But once these changes became more mainstream, I adapted my standards too. And this won’t be the last time; I still have a lot to learn about the intersection of gender, race and language.

I first learned about this capitalization development on Instagram; a testament to the platform’s reach and role in social change. See the post on PR Girl Manifesto.

As content creators, knowing about these kinds of changes allows us to write about a wider range of topics. Not knowing about (or not recognizing) them limits us both professionally and personally. We have to keep up—not only to avoid mistakes, but also to keep our writing relevant, respectful and reflective of the times we’re living in.

Punctuating a pandemic

2020 has been largely defined by the coronavirus pandemic. Brands have had to respond to this crisis in a multitude of ways, including their internal and external communications. While the world considers how to live during an unprecedented global catastrophe, marketers and content creators are faced with another question: how to write about it.

First of all, what do we call it?

Is it coronavirus, Coronavirus, the coronavirus, the new coronavirus, covid or COVID-19? It depends on who you ask. The AP Stylebook has its own take, which can be at odds with the standards established by publications like The New York Times. The trick is to pick a style guide and stay consistent—a tip that applies to creating quality content in general.

Why does this matter? Subtle distinctions in capitalization and phrasing are important because they reflect different perceptions and understandings of the virus itself.

Making the effort to do your research and find the correct terminology shows that you care about accurately representing it—and the way you represent it depends on context and intentions. For example, referring to it casually as “Corona” or even “rona” downplays the gravity of the situation, and calling it “the Chinese virus” stokes xenophobia and hatred.

What does “corona” actually mean?

As someone who speaks both English and Spanish, I’ve thought a lot about the word “corona” itself. It’s a normal, everyday word in Spanish (which originates from Latin), meaning “crown.” This is no coincidence; according to the CDC, “coronaviruses are named for the crown-like spikes on their surface.”

However, if you were to ask the average English-speaking American what “corona” meant pre-2020, they’d probably point to a certain Mexican beer brand (with a crown on the label). Corona beer has actually managed to build brand equity during the pandemic,despite rumors to the contrary and early confusion about this unfortunate association.

This kind of linguistic symbolism is an integral part of how we understand the world. Although it may seem abstract, it has very tangible consequences on everything from brands’ success to public health outcomes. The coronavirus crisis is a reminder of this, and of how these symbolic associations vary greatly depending on what language(s) you speak.

Writing about race

When George Floyd was killed by a Minneapolis police officer on May 25, 2020, nationwide protests broke out—which soon turned into a global revolution. The Black Lives Matter movement has been around since 2013, but this year it’s reached unprecedented levels of support and controversy. And it’s inextricably linked to language.

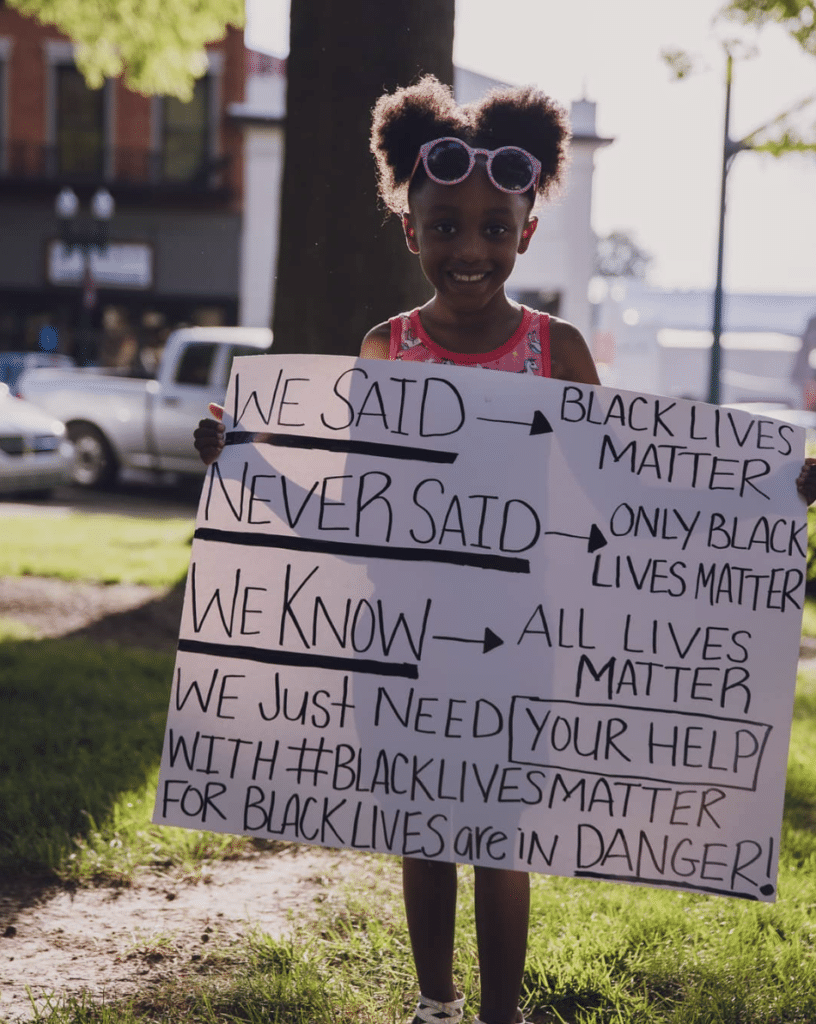

To begin with, there’s the name of the movement itself. The phrase “Black lives matter” might seem simple enough, but the past few months have proven quite the opposite. It’s constantly debated, relentlessly challenged and inevitably counteracted with the phrase “all lives matter.”

While both of these statements are technically true, they can’t be taken at face value. The simple logic of “Black lives matter” is precisely the point. It highlights the fact that this basic truth needs to be affirmed in the first place.

“All lives matter” doesn’t work the same way. There’s no need to highlight the point that all lives matter, because not everyone is being unjustly targeted by police; Black people are. By diverting focus away from that fact, the phrase diminishes its importance. And that has consequences, whether or not the speaker fully understands the implication of their words.

How do you define racism?

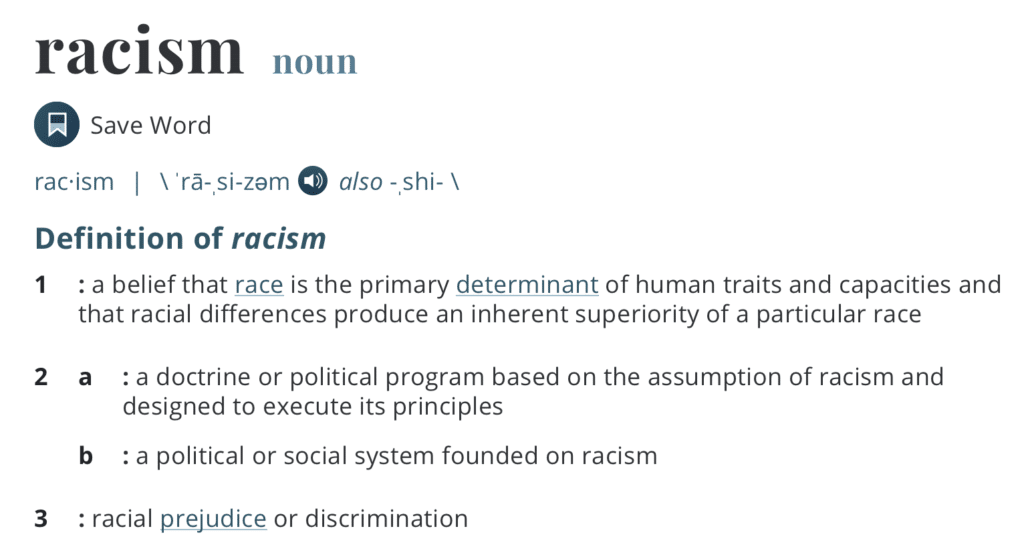

A few months ago, I reposted an updated definition of the word “racism” on Instagram, via the Alberta Civil Liberties Research Centre. This organization argues that racism is distinguished from racial prejudice by the presence of power: “racism = racial prejudice + power.”

A friend was quick to reply and challenge me: “Isn’t that the definition of systemic racism?”

I had to stop and consider this. Subsequent research revealed that according to some people, he was right; but according to others, so was I. It reaffirmed the fact that meaning depends on context, and there are many different ways to define any conceptual term—especially one as loaded as “racism.”

So who gets to draw the lines between racism, racial prejudice and other related terms?

People often use the most mainstream definitions to back up theoretical arguments about race and social justice. Who better to serve as a definitive authority than the dictionary itself?

But plenty of people have taken issue with the way “racism” is commonly defined. In June, Merriam-Webster decided to update its definition of “racism” after a 22-year-old student wrote in to its editors. She argued that racism is not only prejudice due to skin color, but prejudice combined with social and institutional power.

According to one of Merriam-Webster’s editors:

“The usage of racism to specifically describe the intersection of race-based prejudice with social and institutional oppression is becoming more and more common among English users… While our focus will always be on faithfully reflecting the real-world usage of a word, not on promoting any particular viewpoint, we have concluded that omitting any mention of the systemic aspects of racism promotes a certain viewpoint in itself.”

That last bit is important. Merriam-Webster’s goal is to reflect real-world usage and manifestations of meaning. In other words, it’s a descriptive dictionary, not a prescriptive one.

This is a fundamental distinction in the field of linguistics: should linguistic documentation tell us how to speak and write, or should it describe how we actually speak and write?

Even if you take a descriptive approach, you have to recognize that official standards can and do influence the way people think and act. That’s why it’s essential to continuously reexamine the rules that govern language, and challenge those that may implicitly support inequality.

Language, power and politics

In a previous post on why brands should speak out on social issues, I discussed how the coronavirus pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement are being turned into political issues, which is counterproductive and ultimately dangerous.

Language is also an unavoidably political issue.

The words we speak and write don’t exist in isolation, as much as some people might like to pretend they do. They’re a product of context, of the people who use them and the societies in which they do so. They’re an essential part of how we express our opinions, but also of how we form those opinions.

As a result, language is immensely powerful.

The manifestations of linguistic power change depending on the circumstances, the intentions of the speaker or writer and the interpretation of the reader or listener. It’s a complex, multifaceted and unpredictable sort of power.

Those of us who make a living off words are especially well aware of this. After all, you can use words to make someone buy a product or click on a link. But you can also use them to make someone vote for a candidate, take up arms against an enemy or just stay at home.

In other words, language matters.

Every public health crisis, political conflict and social revolution is built partially on a foundation of words. People protest, fight, argue and apologize through words. Quite literally, words can kill—but they can also save lives (and I’m not just being dramatic).

As Chip Kidd puts it:

“In the right hands entire universes are born out of just a few sentences, and can be just as quickly destroyed.”

Never stop adapting

One of the most valuable skills to cultivate, as a professional but also as a person, is the ability to change your mind when presented with new information. This is applicable to everything from politics to personal relationships, and of course to language.

Before this year, I never would have thought to capitalize “Black” in my own writing. I couldn’t have imagined that terms like “PPE” and “quarantine” would roll off my tongue as easily as “YOLO” did six years ago (yikes).

But life—and language—is about evolution.

We have to keep learning and adapting to the changes around us, even when they’re incredibly hard to accept.

We have to remember that words are not inconsequential bits of sound and symbols to be thrown around haphazardly, but units of immense power that collectively construct our realities and identities.

Language is symbolic in more ways than one. It’s a manifestation of power and privilege, and a reflection of our most basic beliefs. As writers, speakers and communicators of all kinds, we have a responsibility to keep up with its changes, adjust our usage accordingly, and always invest an effort in choosing our words well.